By Andrew Barker. At the first full blush of his commercial powers in the early 2000s, Pharrell Williams made a specialty of soundtracking second acts. For rappers with strong street reputations but no hit single to their name, rock frontwomen looking to break out on their own, or teen starlets desperate to shake off the shackles of prefab pop stardom, Williams and his Neptunes producing partner Chad Hugo were the miracle workers on speed dial.

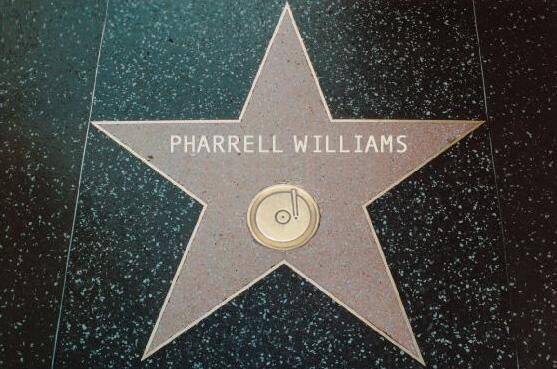

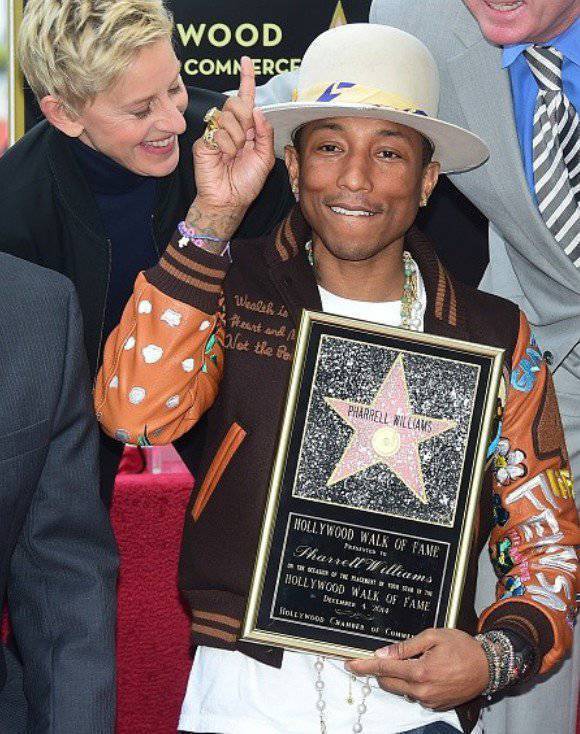

So it’s appropriate that the most recent second act Pharrell has helmed has been his own. A decade after his commercial heyday, when even The Neptunes’ more modest hits were all but ubiquitous, Williams, who receives a star on the Hollywood Walk Of Fame on Dec. 4, bounced back from a comparatively lean period with an explosive 2013. For five straight weeks, Williams had both the No. 1 and No. 2 songs in the country, with Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” and Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky.”

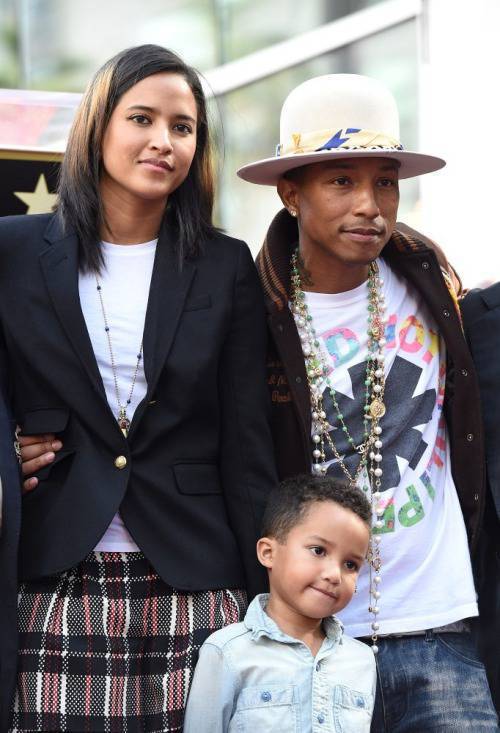

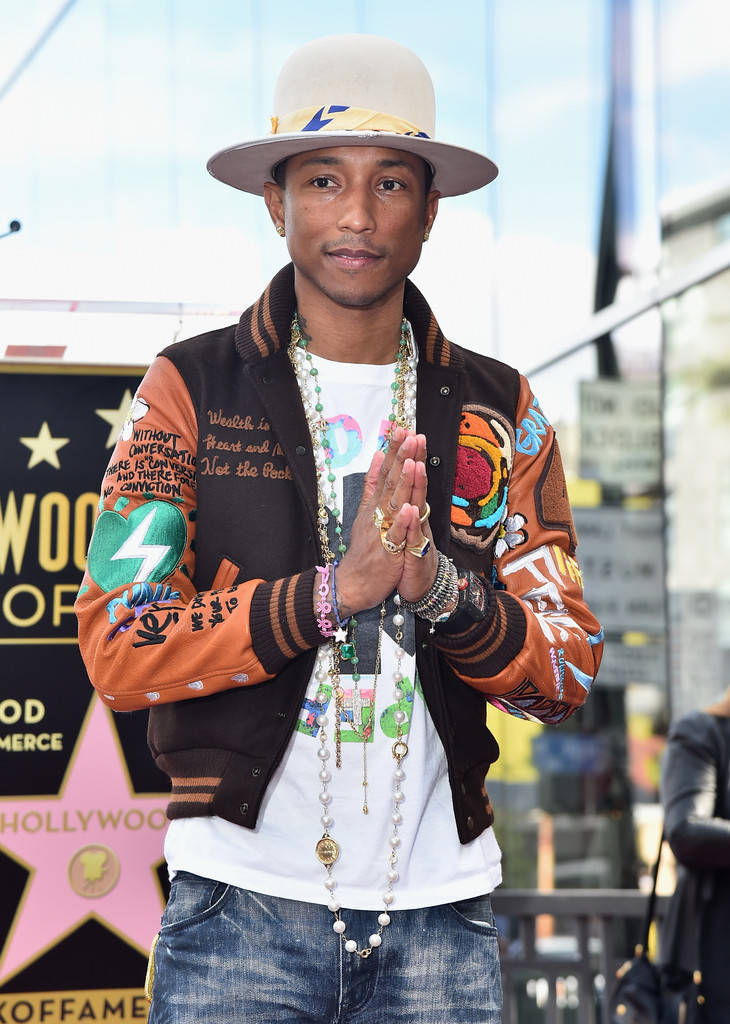

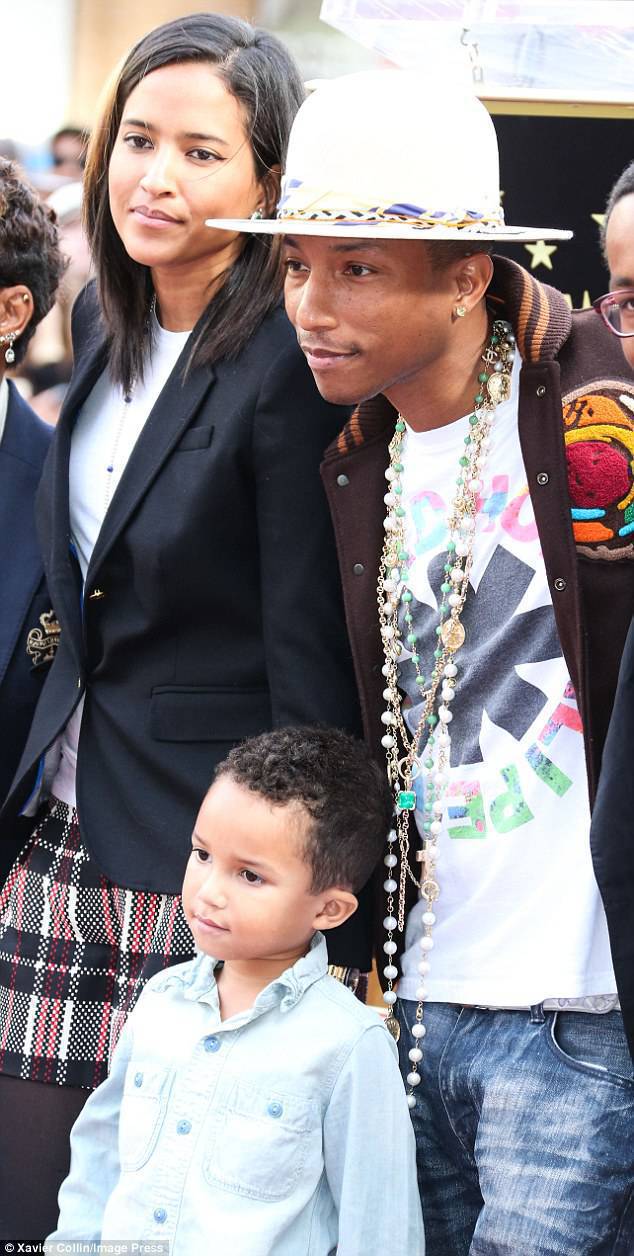

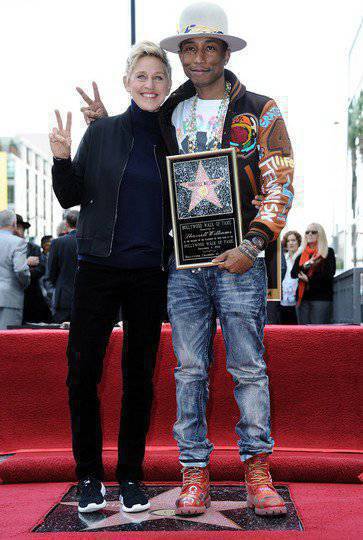

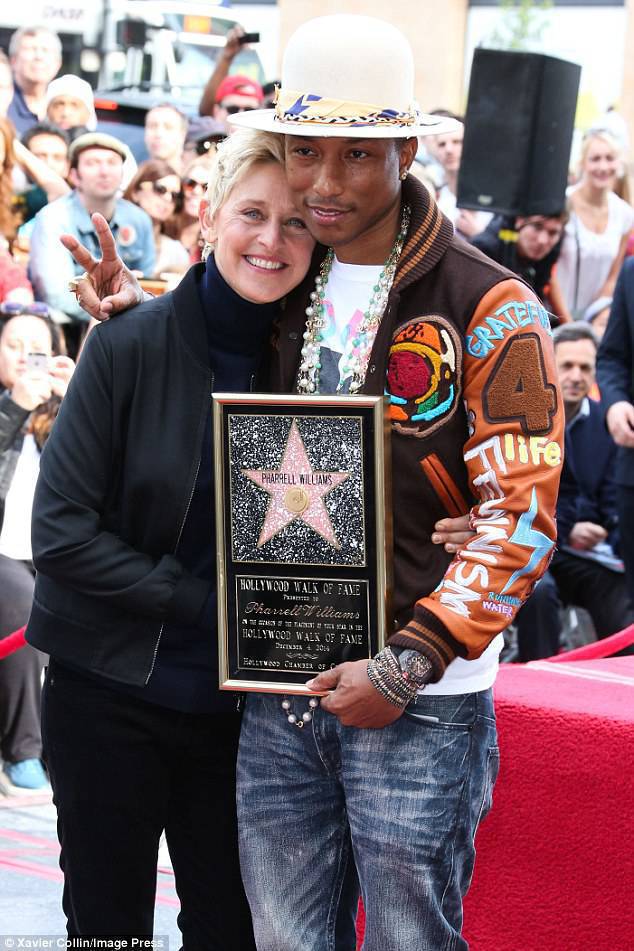

Pharrell Williams Walk Of Fame Ceremony

He won four Grammys at last January’s kudocast, while at the same time “Happy” was on its way to becoming his most successful single as a solo artist, lodging 10 weeks at the summit of the singles chart. A gig on NBC’s “The Voice” followed, where five of his seven fellow coaches have notched hits thanks to Williams’ magic pen.

For all his imposing discography, in conversation Williams comes across like someone you’re more likely to encounter at Burning Man than the Grammys. Sphinxlike paradoxes and words like “gnosis” and “kinesthetic” pepper his speech, and a seemingly straightforward question can elicit a response like “the human mind is literally an antenna, it picks up waves and transmissions from the ultimate source, from the ether.”

Fittingly, Williams takes a figurative approach to avoiding creative burnout. “Being blocked just means that you’re aiming for the same thing as before,” he says, “but your mind is saying to you, ‘there’s no more here. I know you think we can dig deeper with this particular topic or subject, but we’re not going to.’ So you need to go out and hit the reset button, and come back and look at it differently.

Maybe the vantage point with which you were looking at the song or the track was just so acute that it didn’t allow you to see inside the room.” Whatever the reason for the 41-year-old’s reclamation of the pop charts, it feels entirely appropriate that he should do so at a time when the radio landscape has increasingly been retrofitted for The Neptunes’ model. Under the producers’ kingmaking early reign, the distinctions between genres that had previously seemed so strict grew more nebulous.

Working with Williams and Hugo allowed pop stars Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake to sound more like R&B stars; it allowed rappers Snoop Dogg and Jay-Z to sound more like pop stars; and it allowed rockers No Doubt and Fall Out Boy to embrace qualities of both. “When people think categorically, their work becomes categorical,” Williams says. By stripping away the surface signifiers of genre, The Neptunes restored a certain primacy to the beat.

This stylistic flexibility is just as evident now: Even as “Happy” climbed the charts, Pharrell was churning out disco ditties for Beyonce and Kylie Minogue, a buzzsaw beat for Schoolboy Q’s “Oxymoron” and a guest verse on Future’s “Move That Dope.” “I love for songs to be heavier in emotion than in sound,” Williams says. “As long as you have that ability to take a step back so that the work can breathe and talk to you, then you’ll know when you’re done.

But there are some (producers) who just can’t stop. And they’re great at it, but they keep adding things and the song becomes this whole big clunky Christmas tree. It needs to be something that breathes, it can’t be so ornamented. Because underneath it’s still a tree; it’s still a song.” If there was any lingering criticism of The Neptunes’ work in the early-2000s, it was just how easily the hits seemed to come to them.

While lower-stakes pet projects like N*E*R*D’s “In Search of …” and Clipse’s “Hell Hath No Fury” saw Williams and Hugo push themselves into spikier, more abstract directions, their pop hits were so numerous that they all risked coalescing into a sort of sweaty, slithery blur. By the middle of the decade, “Neptunes Beat” might as well have been a preset on a Casio keyboard. “People go to any name brand because they want something familiar,” Hugo says. “I guess it’s inevitable that you start to repeat.”

Repetition is perhaps especially inevitable when one has been working in the same field for so long. Williams and Hugo met when they were both 12-year-olds in Virginia Beach, and eventually fell under the sway of New Jack Swing auteur Teddy Riley. Williams got his first slice of a hit in 1992, when he wrote a verse for Wreckx-N-Effect’s Riley-produced “Rump Shaker,” and he and Hugo began building a resume shortly after.

Ellen & Pharrell

By the time The Neptunes were minting singles for Ol’ Dirty Bastard, NORE and Mystikal, their modus operandi had begun to take shape. Hugo, a high school saxophonist, seemed content to be the guy behind the guy in the studio, while Williams gradually gravitated further toward center stage, appearing in videos for many of the artists they produced, with his adenoidal falsetto often providing the hooks. Indeed, perhaps the only thing surprising about Williams’ ascension to mononymous stardom is that it took so long to happen.

Williams has hardly made any radical departures from formula over the past few years, though it’s hard not to see a certain degree of messiness bleeding through, a willingness to push a track beyond safe limits. His production work on Frank Ocean’s “Channel Orange” and Kendrick Lamar’s “Good Kid, MAAD City” showed him working his way toward a jazzier, more impressionistic register. Even “Happy,” for all its earwormy simplicity, is hardly cut-and-paste songwriting, coasting on an extended vamp.

Hugo admits that The Neptunes’ current productivity is “nothing like the classic days, when we always had the tape rolling,” yet they’ve maintained a signature style with remarkable fidelity. And for Williams, a self-professed synthesthete, the free-associative process of assembling a track is still very much the same, even if that process might proceed at a more leisurely clip. (For all his aura of effortlessness, Williams notes that he’s working on finishing a track he started 20 years ago.)

“First you go about finding that one spark of inspiration, that one thing,” Williams says of songwriting. “And what happens is, whatever entry point that is, whether it’s an entry into a melody, or a word, or a chord structure, or a beat pattern, whatever it is, there’s always a door there. While you chase through the highways of the melody, the music comes to you. Eventually the feeling of the melody tells you there’s an important connotation here. Those connotations could be happy or sad, or emotional, or betrayed, sexy, whatever it is, it tells you what you’re gonna need. It directs you to start building until it’s done.

“Then it’s literally just stacking layers on, and sometimes the foundation is different. Some people will say you have to start with the drums, or the chords, and you would compare it to building a house, where you start with a foundation. But what I’m saying is that sometimes you can take wherever you are, whether it’s the window or whatever, and say, ‘I’m gonna build the house from here.’”

With “The Voice” still in production, Williams is poised to resume doing what he always does: helming a dizzying array of sessions. He’s committed to producing Snoop’s next album from top to bottom, and he and Hugo are making music for the upcoming “SpongeBob SquarePants” feature. “We’re trying not to think too much in a cartoon sense,” Hugo says, “but more just like a psychedelic, otherworldy type of thing.

If you want to draw a parallel, maybe think of what the Beatles did with ‘Yellow Submarine.’” His partnership with composer Hans Zimmer has already begun to yield impressive fruit and he still has a fashion line, a record label and a charity, From One Hand To Another, to keep him occupied. “There’s always a flow to human activity,” Williams says. “If you stare out at it long enough you can see where it’s going, but you don’t have to go where it goes, that’s the beauty of life. You can go wherever you want to go. As long as you’re armed with that information and remain curious, you can do some really interesting things.”

*variety.com

*theboombox.com

*dailymail.co.uk

*breakingnews.ie

*n-e-r-d.skyrock.com

*sk8brdp.tumblr.com

*fuckyespharrell.tumblr.com