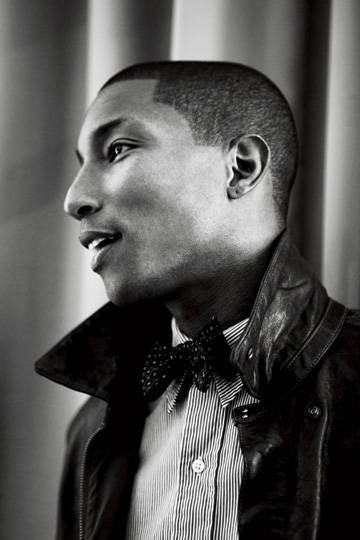

Jake Chessum/Trunk Archive

By Matt Diehl. Music today is more scattered and segmented than ever, but this year one man came out of self-imposed pop exile to create two songs that everyone, everywhere, heard at least once. Pharrell Williams had gone cold. Last year, when Miley Cyrus was starting work on the album that would launch a million twerks, her then-representation suggested she skip working with the one producer she really wanted to work with. To Cyrus, Pharrell was the man who, as part of the producing outfit The Neptunes,

created the sound of the 2000s; who won three Grammys, including 2003’s Producer Of The Year; who helped transform Justin Timberlake and Britney Spears from tween idols into adult superstars. To her reps, he’d become irrelevant. Why not work with one of the armies of producers who manufactured hits for Gaga or Bieber or Katy Perry? Why not go with a producer who’s actually produced a number-one in the past five years? Why Pharrell?

Cyrus got her way — at her insistence, Pharrell came on board as her initial collaborator on Bangerz, her now-huge album — and over the course of a year, he went from self-imposed pop exile to record-breaking ubiquity the way Hemingway wrote about going broke: slowly, then suddenly. Along with Cyrus, he signed on as mentor to Frank Ocean and Kendrick Lamar, contributing key tracks to their acclaimed genre-expanding major-label debuts. He’d also begun working with two other performers, Daft Punk and Robin Thicke, to create songs that, with any luck, would get a little airplay come summer.

The first to debut, Thicke’s easy-breezy sex jam “Blurred Lines,” which Pharrell produced and appeared on, broke every existing record for radio airplay and turned the charisma-challenged offspring of a Canadian TV star into the coolest white man in music. The second, Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky,” cowritten by Pharrell and featuring his radiant, come-hither vocals, became the most streamed song ever on Spotify and made the cult electronica duo a household name. They were the biggest, ballsiest, unlikeliest songs to take over nearly every single radio format in recent and distant memory.

At one point, for five consecutive weeks, “Blurred Lines” was the number-one single on Billboard, and “Get Lucky” was number two — making Pharrell only the twelfth artist ever to achieve such a feat. And what makes it all the more remarkable is that neither sounds much like the other, nor do they sound like anything else on the charts — or anything that Pharrell has done in the past. What the hell had he been doing all those years in the wilderness?

*esquire.com

Stuff, mostly. He was busy running his two clothing companies, Ice Cream and Billionaire Boys Club, as well as designing sunglasses for Louis Vuitton and outerwear for Moncler. He invested in a pioneering, eco-friendly textile company, Bionic Yarn. He and Chad Hugo, his longtime partner in The Neptunes, began working more and more on separate projects, yet his solo efforts never quite reached the stratosphere: His 2006 single with Kanye West, “Number One,” stalled at number 57 on the Billboard Hot 100. Plus, he had a baby boy, Rocket, with wife Helen Lasichanh in 2008; inspired by fatherhood, he produced the acclaimed soundtrack for the 2010 blockbuster Despicable Me. He lived in Miami. He turned forty.

He also had quietly been rebuilding his sonic arsenal, taking a break by going through his hard drives and erasing the sounds that had become his signature. He’s done this kind of thing before; he once told me about having grown too reliant, for example, on the pounding 808 kick-drum preset from the Korg Triton keyboard that drove Neptunes-produced hits like the Clipse’s minimalist rap masterpiece, “Grindin‘,” from 2002. Once that became an identifiable, copyable style, he knew it was time to move forward.

“I love the alchemy of things,” Pharrell says of the impetus behind blending, say, twangy bluegrass and ’90s-nostalgic electronica, as he does on “4×4,” a standout new track from Cyrus. “Iconic artists are never straight ahead. Michael Jackson loved Elvis and Burt Bacharach, and uniquely blended both of them into what he did. Miley, she loves hip-hop, but her godmother is Dolly Parton. Putting contrasts like that together, you’re bound to get inspired.”

He’s always been like that, a little off. When I was compiling an oral history of the creation of Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s 1999 album, Nigga Please, I set up an appointment to speak with the then-unknown producers of ODB’s hit from that album, “Got Your Money.” In an era of hip-hop artists wearing sagging waistlines and throwback jerseys down to the knees, Pharrell and Hugo walked into the room and their clothes actually, you know, fit. They weren’t thugged-out beat boys from Harlem or Compton; they were band-camp nerds from Virginia Beach, Virginia. In lieu of bragging about his dope rides, Pharrell waxed cosmic about blasting Stereolab and Steely Dan in his pickup truck. They seemed like they were from another universe.

Despite this weirdo cred, The Neptunes quickly became hip-hop’s preeminent producers, lacing hits from Busta Rhymes, Fabolous, Snoop Dogg, and Nelly. Pharrell’s voice became a definitive part of The Neptunes‘ sound: His urgent falsetto brought vintage Curtis Mayfield–style soul to bangers like Jay-Z’s 2000 club mainstay, “I Just Wanna Love U (Give It 2 Me),” turning him into a star in his own right. (Pharrell was born with the last name Williams, but as his fame increased, he joined the likes of LeBron and Beyoncé in the recognizable-by-just-their-first-name club.)

In a moment when much in the Top 40 feels as cheap and canned as ever, Pharrell’s recent efforts as a solo producer exude an effortless, decidedly human funk — a little sweat and swing that were nowhere else to be found. ” ‘Blurred Lines‘ isn’t what anyone expected from a pop record today,” says Josh Abraham, a top producer and publishing exec who knows something about the strange science of pop music. “And now that it’s an established hit, everyone’s relaxed — like, ‘Now we can do our Marvin Gaye–sounding songs like we always wanted.’ It reminds me of when Nirvana‘s ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit‘ came out and rewrote the rules. Its most important lesson is that there is no one formula.”

Pharrell’s approach involved not trying to compete with what was on the charts, but instead avoiding the lowest common denominator and employing — gasp! — real instruments and authentic voices working in sync to find the pocket. Yes, his recent productions are seamlessly pieced together with today’s digital technology, but never so much that they lose their authenticity, that spark that makes them crackle. For Cyrus, that meant laying off the Auto-Tune; for Thicke, that meant channeling the loose, slinky groove of Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up” (so much that Pharrell and Thicke are locked in a dispute with Gaye’s estate over plagiarism charges). For Daft Punk, it meant Pharrell singing his ass off like he was a lost member of Earth, Wind & Fire, all while letting his charisma burn a hole in the track.

It’s a risky strategy — letting go of past triumphs, pushing yourself and your collaborators beyond what they think they can accomplish, creating your own lane instead of following the YouTube traffic. But for Pharrell, it was the only way to move forward on his own. “You have to do that soul search, see what’s there, and then amplify,” he says. “Pushing towards that makes for something that feels like lightning in a bottle.” Which, by its very definition, is elusive and unpredictable, but when it happens, the sky explodes and everyone sees (and hears) things in new and different ways. “Everything he did with, like, Justin and Britney made Pharrell a legend,” says Cyrus. “But that wasn’t really his time.” Keep listening.