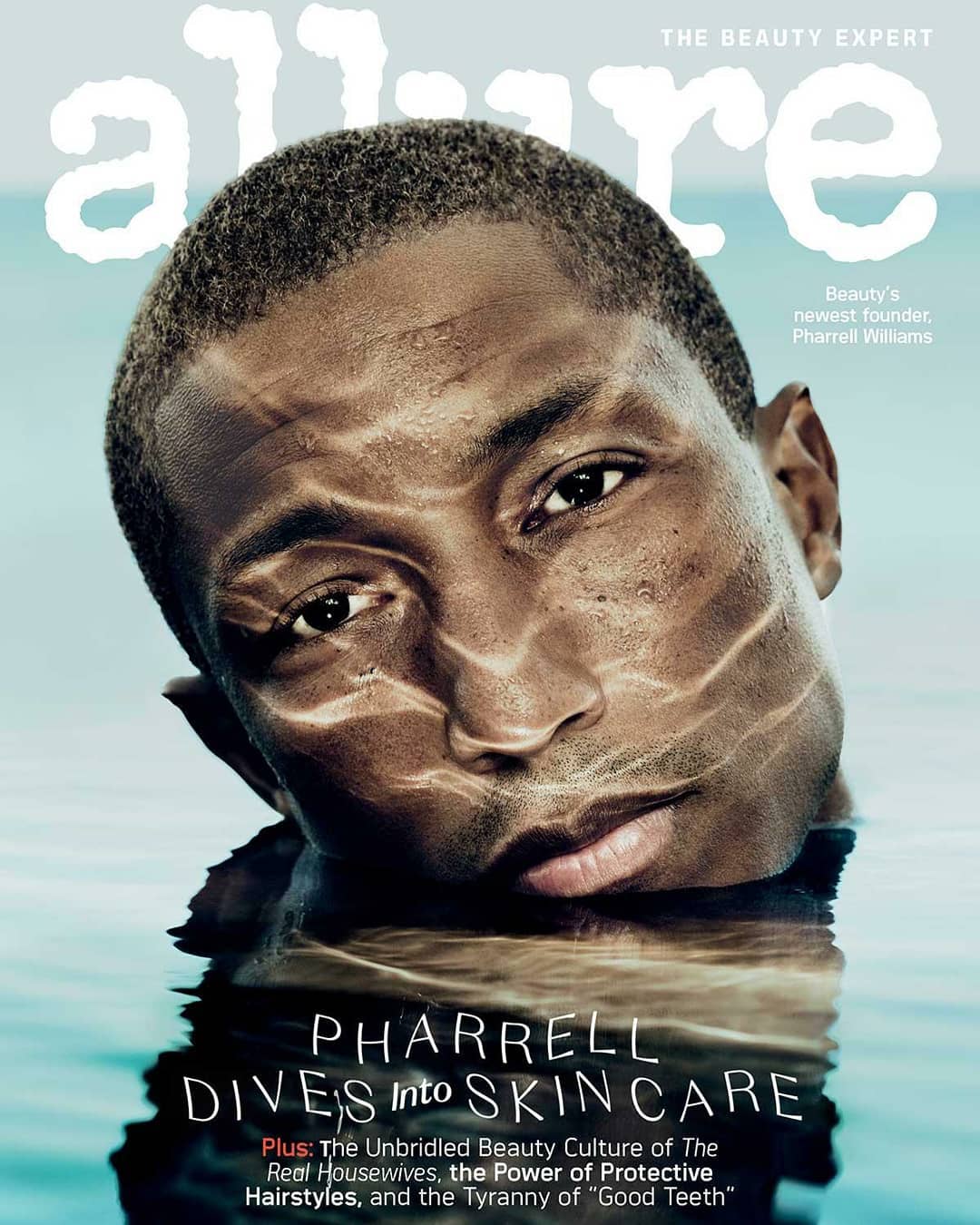

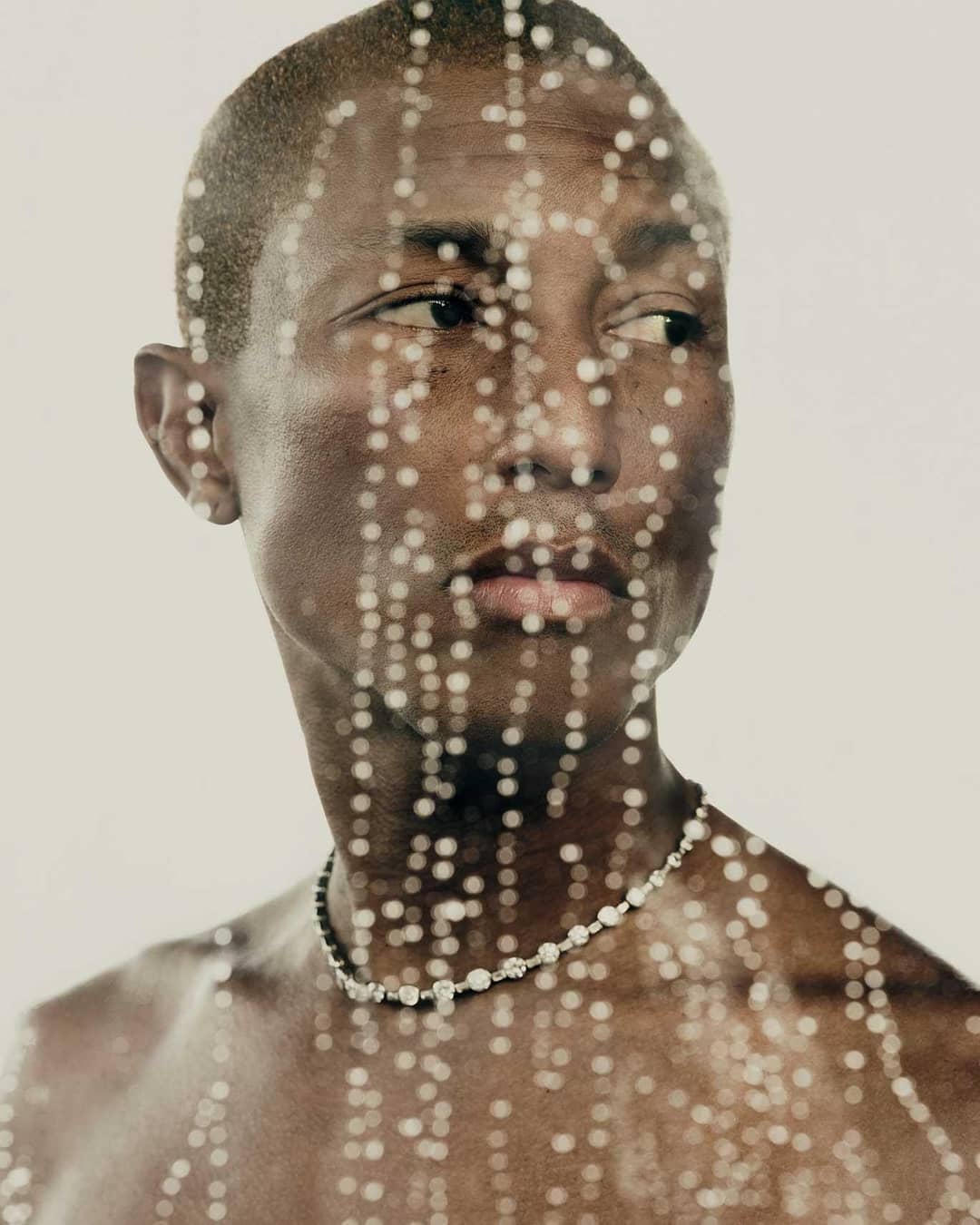

Not so long ago, Pharrell Williams found it necessary to confirm in an interview, picked up by CNN, that he is not a vampire. The suggestion didn’t relate to his supernatural creative output in songwriting, performing, and fashion design. This was about how Williams, 47, on the cusp of entering his sixth decade, looks like a guy who is younger by half. His angular cheekbones are heirlooms from his grandmother. His father gave him almond-shaped eyes. Admiration for his talent as a musician and performer has always been accompanied by a preoccupation with his good looks and skin-care routine. Photos by Ben Hassett for Allure Magazine.

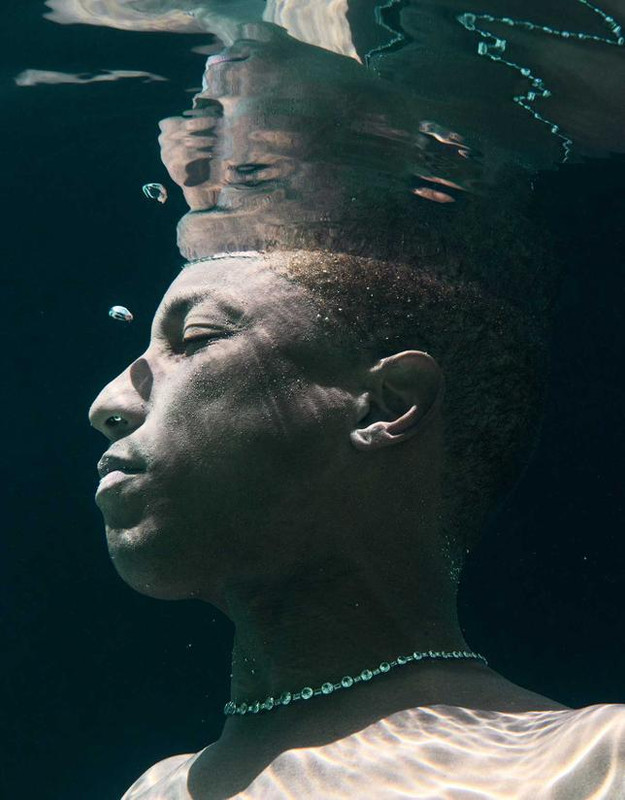

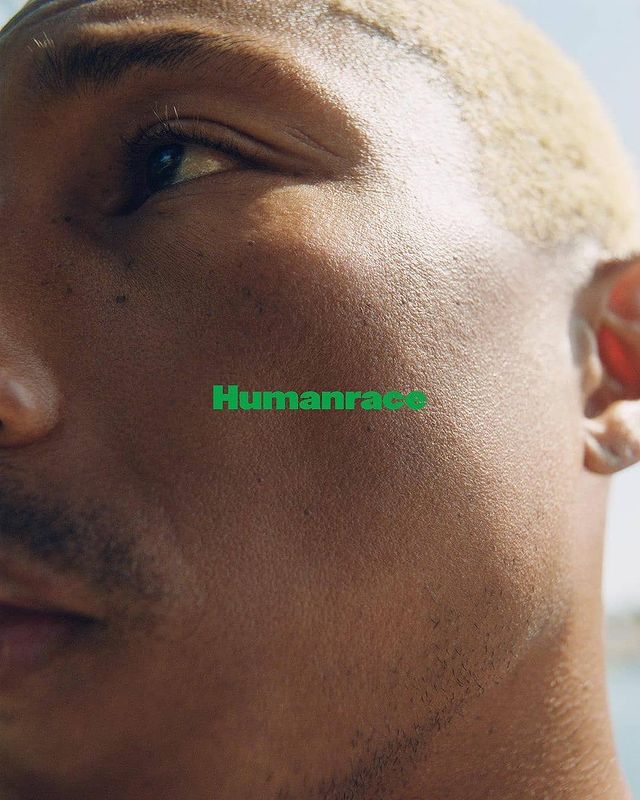

And his sensitive, philosophical bent applies to every category of his pursuits. “Sometimes you need to cleanse your spirit,” he says. “Sometimes you need to cleanse your mind. Sometimes you’ve just got to get rid of some dead skin.” Later he’ll take me along on a bike ride, but for now he appears via Zoom in the middle of his white Miami kitchen, the size of an airplane hangar, to talk about his newest endeavor: a line of skin-care products developed with his longtime dermatologist, Elena Jones. “Are you seeing this?” he says in the tone of a proud father, filling the screen with a squat bottle the color of freshly mown grass. The word “Humanrace” leaps off of the packaging. Williams runs his finger along the name and gazes satisfied into the camera, attempting to send the tactile experience telepathically to my own nervous system.

Humanrace Skincare launches with a rice powder cleanser, an enzyme exfoliant, and a “humidifying” moisturizer. “I grew up in humidity,” he says. (He was born in Virginia Beach, less than a mile from the ocean.) “The way I think about things… I’m an Aries, but I’m also a Cancer rising. Water makes me feel free. Water is very inspiring to me.” In fact, it’s kind of a lifelong theme. “I’ve always been obsessed with the idea that water falls [from] the sky as evaporation,” he says. Williams’ ability to market water to the Atlantic or sand to the Sahara is always on display. To that point, he produces a loden-green sandal and thrusts it into the webcam. It looks like a shower slide wearing a puffy tube top. “I told everybody, ‘Listen, wearing these are like [wearing] socks,’” he says. I look them up: Adidas x Pharrell Williams Boost slides, $100 a pair. “And they sell out, because people want comfort.”

If you wanted to invent a title for him, Williams is Humanrace’s chief sensations officer. He defines his particular skin-care expertise as a talent for being able to “describe sensations,” which are then reverse-engineered by his team, making previously nonexistent experiences real. Like the experience of wearing shoes that grasp your feet with the gentlest of embraces, or the feeling of humidity on your face, but in a cream that also glazes your cheekbones. “You put on that humidifying cream.” He grins and his little black mustache goes flat. “You’re like, ‘Oh man, my skin is popping.’”

Beneath the unrelenting Miami sun, where the air is so wet that it could be bottled and sold as a moisturizer, Williams goes for a bike ride a couple of times a week. He started biking around Miami 15 years ago, as a physical and spiritual exercise. The cardio from riding some hundred miles a week keeps his skin close to his frame. “I like to be slim,” he specifies. “I don’t want to be bulky. I don’t want to have big muscles and shit. Like, I’m not looking to be some Greek statue.”

Williams is riding south. I ask a few times where he rides his bike, hoping he will respond with fabulous local imagery of Miami, but his answer is always the same: He rides south. He rides south until he’s done riding south, and then he rides north. At the beginning of the ride he curses the wind, but minutes later he is overcome with the sensation that the wind is, in fact, a divine force propelling him forward. “You realize that there is something much more than just you, your bike, and your attention to where you’re headed. There’s this force that comes from nature that you just… If you’re down to be in tune, it speaks to you. It speaks to me.” He rode his bike all the time while growing up in Virginia Beach, probably not looking much different than the way he does now, slim and boyish. South and north.

He began a serious pursuit of skin health in his mid-20s; during the early days of his career, he engaged in impromptu grooming summits with women he dated or befriended or met professionally. “They’d talk to me about their skin and the things that they’d do,” he says. “It varied between the different girls and campaigns that they had done and what they felt was integral to their process.” He remembers a bouquet of skin-care advice from Naomi Campbell: “‘As soon as you’re done washing your face, you wash it with cold water.’ She would always talk to me about never washing my face with the downward strokes of whatever cloth I was using, to always go upward, to go against the gravity.”

The celebrity network is both the best and worst place to seek out skin-care advice. On one hand, celebrities are fluent in skin care, in the way an American soldier stationed in the Philippines might be fluent in Tagalog; but many celebrities are contracted by beauty companies to limit their expertise to a particular brand or product. They are often not reliable narrators. Williams’s explanation of his skin-care line is perfectly Pharrell-y: “Humanrace is a full-on brand,” he says. “We just want to make things better. We want to democratize the experience of achieving wellness. And I’m not trying to be like any other wellness brand out there. That’s what they do. That’s what they give. Ours is all based on results and solutions and sensations. We wanted to look at sensations. I mean, we live in a world that needs it.”

In previous interviews, Williams has been careful to point out that he is not primarily an activist. But this past summer, shaded by the Movement for Black Lives, his thinking has evolved. He’s been particularly inspired by Michael Harriot and Henry Louis Gates Jr. — their writing has shown him that effecting powerful, meaningful change can be done in myriad ways. “Gates said, there are many different ways to protest, to be on the front lines,” Williams says, referencing protests that have occurred all over the United States since May. “Some people are great orators. Some people are great strategists. Some people can stand and hold a placard, protest sign, for way longer than other people. There are people making sandwiches and bringing nourishment to people who are out there. My activism has [taken a lot of shapes]. Because my culture, our lives matter.”

This summer, Williams and Jay-Z dropped “Entrepreneur,” a song that enumerates the ways in which capital is taken from Black men. In Times Square in New York City, the phrase “Black Man” towered into the sky from a New York Police Department outpost, promoting the single. When I ask Williams if the song is inspired at all by his business success, he demurs. “I mean, Jay and I just did that song as a PSA,” Williams says. “Only. It’s just that.”

The song is, as Williams explains, intended as kindling for aspiring Black business owners to stoke the flames of ambition within them. Or something. He puts it like this: “[When] you hear the whispers of your ambitions, act on them. You’ve generationally been told how tough it’s going to be for you. It’s like you’re on the baseball team, with one arm behind your back. You might be able to catch the ball. How far are you going to be able to hit it? They need you to be able to make it all the way home.”

Williams has made it home. He has written or produced or performed at least one of your favorite songs. He has made songs that made you run from the bathroom to the dance floor, back in an era when people did so, clenching your pelvic floor through the opening chords of “I’m a Slave 4 U” and “Hot In Herre.” His earliest work producing tracks with Chad Hugo was obscured by the mononymous stars who performed them — Britney, Justin, Nelly. When music journalists became aware of the fact that two men from Virginia Beach were responsible for one out of five songs playing on pop radio, they were delighted and intrigued.

How does Pharrell Williams make music? “It’s like a house,” he says. “There’s more than one way inside the house. It’s not just the front door. The side doors, windows, patios. There [are] so many ways, so I don’t know that we have the time to —” We do not. We are on minute 50 of a very tightly scheduled second interview that had to be conducted during Williams’ workout. The first interview occurred while he was in the middle of working on Rosalía’s third studio album. He had to politely excuse himself, briefly, in the middle of giving an answer to wish her farewell.

“— really unpack that. I will say that no matter the scenario, when it comes to music for me, there’s always a trigger. It’s just a word in the conversation or a notion, or seeing a situation, or watching a movie. It all depends. And once you find that trigger, it becomes a rabbit hole and then you just kind of go down that. The rest of it is figuring out what the groove is going to be.”

He and Hugo are currently helping engineer the groove for Rihanna’s thirstily awaited ninth album. “Rih is in a different place right now. Like, wow. She’s from a different world.” Williams claims that this world might be Venus, which he supported with recent suggestions that there might be life on Earth’s next door neighbor. “I‘m willing to bet, because Venus is gaseous, that if they had a telescope that could zoom through all that shit, you’d see Rih laying there naked.”

Williams has the bewildering ability to make music that is excellent and popular. In the past decade he scored two 10-week-plus Billboard Hot 100s, for “Blurred Lines” and “Happy.” The former was a funky jam that many critics felt condoned sexual assault — Williams’ eyes have since been opened to their interpretation of the song — and the latter was wildly popular on the baby shower circuit. Williams’s groove changed with “Happy.” The song was less an essential creative endeavor than it was a line item to be delivered to Universal Pictures for the film Despicable Me 2. CeeLo Green was originally supposed to provide vocals, but his team passed on the opportunity. There is a parallel reality in which our nation’s CVS pharmacies are filled to the brim with the astringent vocal stylings of CeeLo Green explaining how joyful he is feeling, asking us to share in his revelry.

But that is not the world we live in. Williams ended up recording “Happy,” his honeyed voice coating its syllables, hardening into sonic gold. The song’s dizzying catchiness and core themes of happiness, gratitude, and dancing helped Williams conquer America’s children under 10 and the white elderly. It probably granted him a new valence of fame. The song was commissioned by a movie studio for a different artist, but like many Americans do every day, Williams simply aced a work assignment that, for better or worse, became his legacy.

Back on the bike ride, south and north, as we’re talking, a woman shouts in the background. “Hey! Is that really you?” Still in motion, Williams thanks her. “Did you hear what she said?” he asks me. “She said, ‘I’m so happy.’” We had just been talking about his mixed feelings about that song, and there is a pause about the length of a modest blush. “It was like Black Mirror for me, bro.”