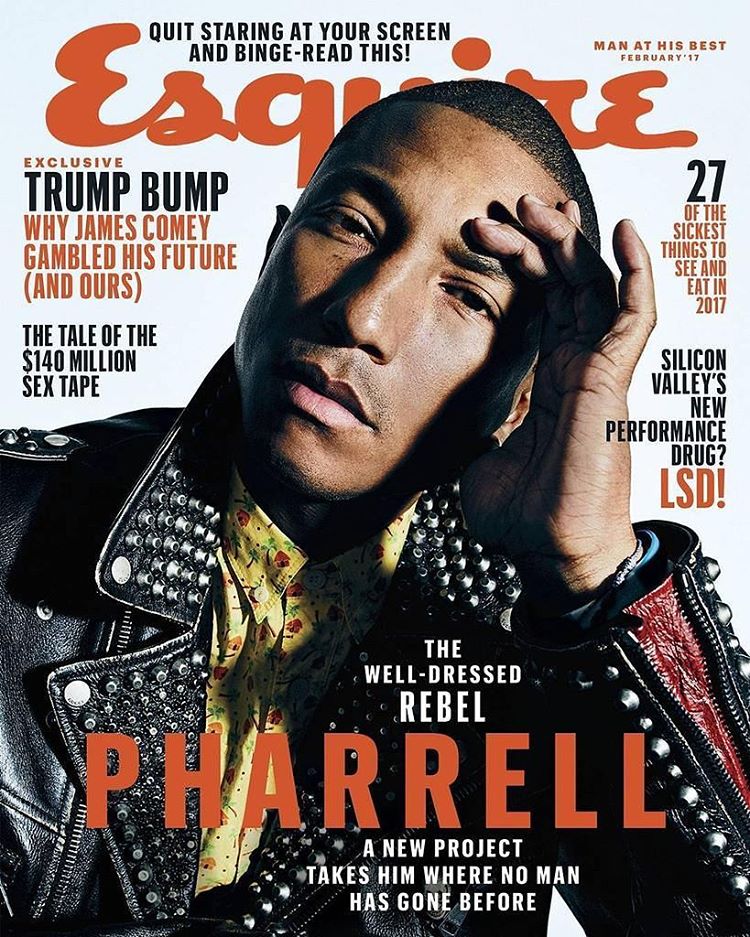

Photos by Mario Sorrenti. Pharrell Williams Is Ready to Question Everything. Pharrell is one of our most multidimensional artists—and the guy who gave us one of the peppiest pop songs of the past decade. But on the heels of a new album, a movie, and a sea change in politics, he wants the script to flip. He doesn’t really write the songs. You understand that, right? Of course. Pharrell has written so many songs that it may, at this stage, be impossible to track and tag them all. But he’d like to dispute the whole concept.

Pharrell listens. He listens for signals. He receives the songs. “I think everything is given to us,” he says. “Everything is. We didn’t create it. It’s being given to us in one shape or form. It is a deep delusion to think otherwise. I’m not the juice. I’m not the ice that makes it cool. And I’m certainly not the glass. I’m just the straw.” Which is not to say that being the straw is easy. To get the songs, you have to pay attention. “The greatest gift is self-awareness. That’s when you realize the beauty of life. If you’re not self-aware, then you’re lost.”

A golden sphere of sunshine is rising over L.A.’s San Fernando Valley. We are about to fly into the open arms of history. Or at least we think we are. We feel a surge of possibility as Pharrell—the “Williams” strikes you as a pointless formality at this point—pulls up to an airport in Van Nuys and boards a Gulfstream IV that will carry him and members of his team to Raleigh. There, as the golden sphere of sunshine sinks on the opposite coast, he will stand on a dais with Hillary Rodham Clinton and Bernie Sanders five days before the United States of America then appeared (as the tracking polls morphine-dripishly tell us) poised to elect its first female commander in chief.

He will give a speech. He will rally the troops. He will raise the roof. Pharrell has been summoned, and there’s a certain kind of logic behind his command performance on the campaign trail. He is forty-three, with an eight-year-old son, Rocket, and a wife, Helen Lasichanh, who is pregnant with their second child. But he could pass for twenty-three, and those who know him through the filter of his signature earworm, “Happy,” see him as a vaguely extraterrestrial ambassador of just that—happiness.

One might say that happiness itself is being summoned to Raleigh, with Pharrell serving as its most recognizable and proficient vessel, and not a moment too soon. For decades now, one of the defining theories of American politics has been that of the Happy Warrior. This is the belief that it is always the more joyful of the candidates (Reagan, Dubya, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama) who winds up occupying the White House. But such a divining rod seems useless in these waning days of the weirdest election in American history. Neither candidate seems remotely happy. Nobody is happy.

So as Pharrell, outfitted in a gray Human Made hoodie and floral G-Star trousers, arrives at the Van Nuys airport with his retinue, and as a Fox News promo clip in the waiting area barks, “We’re five days away and the race is tighter than ever,” it’s all too easy to lay this out as some kind of superhero narrative: Dr. Happy is coming to save the day, armed with a vial of the magic elixir that sweetens and deepens every piece of groove candy he has ever touched. (And, er, maybe he’ll help with black voters, too. Beyoncé and Jay-Z will climb aboard the HRC train the following day.)

Pharrell’s presence in songs, and over four seasons on The Voice, might lead you to think there is something ethereal and detached about the guy; like George Harrison, he gives off an aura of having logged serious hours in the spirit realm. But he is, in person (as was said of Harrison), tougher than you’d expect, a lot funnier, and surprisingly talkative. He says he is tired, but he doesn’t seem tired; he says he doesn’t exercise much beyond some sun salutations in the morning, but his frame and his posture suggest a built-in athleticism.

His creativity is all about making connections, seeing what happens when you mix A with B and X with Z. He’s omnivorous about music. He says he’s been listening to a lot of ’80s punk; he mentions offhand that he might someday collaborate with Donald Fagen of Steely Dan. If we’re talking about building walls versus building bridges, Pharrell is way over on the Golden Gate side of the spectrum. Here on the plane, at least, he is not some sphinxlike mystic, and frankly he makes for a pretty ambivalent politico. “I’m not a huge trust guy when it comes to politicians.”

He cites his early work with N*E*R*D, back in the dawning years of this century, when his lyrics were more caustic and questioning than his mainstream fans may realize or remember. He has had his disagreements with Team Hillary about the direction of the campaign. He’s not altogether cool with being called a “supporter“; he’s “a supporter with opinions,” he corrects me. As the Gulfstream starts to gain velocity on the runway, Pharrell says, “Hold on a second,” places his hands together with his fingers pointed upward in a gesture of prayer to God, and closes his eyes.

When we’re in the air, crossing the dry gullies of the American West, we mostly talk about women. It turns out that what energized Pharrell—what got him to cancel studio time and fly to North Carolina—is his belief that it is high time for women to take the lead. “Let us experience that,” he says. “I don’t know what I could do, but I know if women wanted to, they could save this nation. If women wanted to, they could save the world.”

Pharrell expresses so much reverence toward women that it’s not hard to imagine that he was praying to one when he placed his palms together during takeoff. (Hey, he doesn’t receive those songs from just anywhere. Pharrell grew up Christian and makes no bones about his belief in a higher power.) “Women have a lot to carry, right?” he says. “Including the entire human species. That’s deep. And still they don’t have an equal say on this planet. That’s insane. Meanwhile, their feelings are suppressed, their spirits are oppressed, and their ambitions are repressed.”

Pharrell’s feminist inclinations fueled his latest endeavor, Hidden Figures, a film he worked on as a producer and wrote original music for. The movie tells one of those stories from the course of American history that you can’t believe has gone unheard for so long. Directed by Theodore Melfi and starring Taraji P. Henson, Octavia Spencer, and Janelle Monáe, it raises a toast to three African-American women (Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson) who worked at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia, where they played pivotal roles in America’s space race against Mother Russia in the early 1960s.

Without their breakthroughs in mathematical formulas, computer programming (then in its infancy), and engineering, astronaut John Glenn may never have made it into orbit—nor would he and his capsule have splashed down successfully near Grand Turk island. For decades, their story wasn’t merely marginalized; it was unknown, not even a blip on the radar. No one was listening. “The female contribution to anything significant has always been historically dismissed or discounted, or often erased,” Pharrell says.

To a degree, the women were unseen and unheard within the white management structure of NASA, even while they were in the midst of making the calculations that would eventually send American astronauts to the moon. The movie has a series of scenes in which Henson, playing Johnson, has to totter frantically in high heels to a building far away from the main Langley war room because no one thought, in those last days of segregation, to provide a nearby restroom for black women. “That’s how rigged the matrix was,” Pharrell says.

“One of the great things about Pharrell is he is open to knowledge all the time,” says Hans Zimmer, the prolific Hollywood composer, who has worked with him for years. “He’s a great listener.” When the two were collaborating on the score for Hidden Figures, they wanted the music to sound different from the Coplandesque Americana that usually powers through astronaut flicks like The Right Stuff and Apollo 13. Whereas the trumpets in those films tend to come across as patriotic and triumphal, “we needed to infiltrate this music with an African-American sound,” Zimmer says.

They wanted more of a muted echo of Miles Davis. “Pharrell took this whole thing a stage further, as he always does,” Zimmer says. Pharrell decided that the orchestra performing the movie’s score should include as many female and African-American musicians as possible. “We flew people in from all over. It was the right thing to do.” With the original songs he contributed, Pharrell manages to inhabit a lost era: Imagine him slipping into the skin of early Smokey Robinson and you have a sense of what the album feels like—they’re nuggets of R&B from some collective lingering dream of the sixties.

Yet, as with one of the first singles, “Runnin‘,” they’re full of that instantly recognizable Pharrell DNA. The music lives in both the present and the past. A number of factors drew Pharrell to Hidden Figures—not just a plotline celebrating the unsung accomplishments of women of color. The story takes place in a part of Virginia that’s about twenty miles from where he grew up—Pharrell readily identifies as a southerner, and he advised Melfi on how a scene at a church barbecue should look, sound, and smell.

Plus, the movie features a personal obsession of his: outer space. He’s a Star Trek nerd, and one of the fashion brands he’s associated with, Billionaire Boys Club, uses the helmeted head of an astronaut as its logo. When we get to Raleigh, where Pharrell will pump up the crowd as the opening act for Clinton and Sanders, a photograph of Carl Sagan will be taped to the snack table in his dressing room. Yes, this is a man who has “photograph of Carl Sagan” in his contract rider. When he says he got involved with Hidden Figures because “I guess the universe was just leading me in that direction,” you get the impression that he means it literally.

Is the universe beckoning him to North Carolina? It’s hard to say. Remember, when all this is happening, we’re still in a big, shiny bubble—we’re days away from the stark realization that Clinton was not a shoo-in. Pharrell’s on this plane, heeding this call, because what choice did he have, really? “I did it so I could sleep,” he says. “So whatever happens, I know I tried. This has kept me up at night. The kind of divisions that this nation is seeing—it hasn’t been this way since the sixties.” He thinks it’s time for men in particular to wake up and hear what women are saying. “Listen,” he says. “Because we don’t. We don’t even listen to ourselves.”

He stretches his arms upwards. He’s tired. “That Japanese jet lag, man,” he says. Just a few days ago, he got back from one of his many trips to Japan. (“Japan is like a creative power pellet,” he says.) Before the plane lands at the Raleigh–Durham airport, Pharrell will lie down on a couch and take a nap. But in the meantime, he has more work to do. “You got the speech?” he asks his team. “I wanna go check that out.” He huddles at a table with Caron Veazey, his most trusted advisor, and they fine-tune the music of the stemwinder that he’s set to deliver to voters in a matter of hours.

A map on the wall tells us that we are flying over Paducah, Kentucky. Were Pharrell to peek out the window, he might be able to see all of the states, even on the horizon, that are on the brink of handing their Electoral College sum to Donald J. Trump. Wherever the hell we are, it feels eons away from 2013. That was the year when Pharrell’s presence in the universe was so dominant that it seemed as though scientists were going to need to add a new chemical compound to the periodic table of elements: Pharrellogen. In 2013, we got not one but two juicy songs of the summer: Daft Punk’s dance-floor magnet “Get Lucky” and Robin Thicke’s controversy magnet “Blurred Lines,” both of which had the properties of Pharrellogen woven into their DNA.

Later that same year, we heard the Pharrellogenic falsetto animating “Happy,” a song of such childlike, hand-clapping, hat-wearing bliss that resisting it would have been like resisting french fries and puppies. So ubiquitous was “Happy” that its association with the kiddie film Despicable Me 2 would come to feel like a Wikipedia footnote. Three years later, we’re slogging through the age of Deplorable Them. Disenfranchisement and frustration will, on Election Day, play a major role in propelling Trump into the White House.

As will become clear in retrospect, it’s not just that the Clinton camp failed to spread happiness; it’s that the Clintonites were too Beltway-coddled to recognize all the unhappiness. Strangely enough, when I bring up “Happy” and its origin to Pharrell, he wants to talk about unhappiness instead. “I started thinking about other people,” he says of 2013. “I noticed that there was a lot of pain going on around the world.”

When that song became as widespread as a golden sphere of sunshine in southern California, people would come up to Pharrell and thank him for it, but they would do so with an undertone of melancholy, even desperation. He was taken aback. “Then you start thinking about why they might have needed that song, and it becomes very heavy,” he goes on. “And so it was an awkward time.” The plane lands in North Carolina around 5:00 p.m. We sit on the tarmac for a while. There is a strict Secret Service protocol regarding movement, so we stay put.

We are joined by Michelle Kwan, the former Olympic figure skater, who has been working as a liaison between the Clinton campaign and celebrities. Kwan serves as our guide; we all pile into a van. Pharrell sits silently, right behind the driver. Someone in the van murmurs something about “cynicism,” but Pharrell mishears the word as “synesthesia,” which is perfect. “I have that,” he says. When his ears hear music, it manifests itself visually as well—he sees colors and images. We are told that a scrum of photographers will be waiting and that only Pharrell will be able to go inside the Stronger Together plane.

Pharrell turns around and looks as though he is about to say something profound, something that will illuminate this experience of preparing to hang with someone who might be our future president. He places his palm out. “Tic Tac,” he says. He’s given a mint. The van pulls over to a different area of the tarmac, next to a cluster of Raleigh police officers with buzz cuts and sunburns. A Secret Service agent pops his head into the van. He gives us lapel pins that signify security clearance and stresses that we really do not want to lose them—if we were to do so, things could get messy. We should be careful.

“These things are flimsy,” he jokes. “The government bought ’em, so . . .” Pharrell steps out. We watch him climb the staircase leading into the Stronger Together plane. We wait. Eventually, he comes back out with Clinton and photographs are taken of them chatting at the top of the staircase. It all looks very happy and breezy, but when Pharrell gets back into the van and Kwan takes the front passenger seat, it’s clear that he did not view this meet-and-greet with the former secretary of state as some routine photo op.

Pharrell did not come all this way just to smile for the crowds. He has something to say. He is hoping someone will listen. Pay attention to his cadence and you can tell that he is not sure this whole thing is going to work out. “This has been my problem with the campaign,” he tells Kwan. “We’re not being realistic. We’re being idealistic. We’ve got to be realistic.” As the van starts pulling away from the Stronger Together plane and moving across the airfield, you could say that Pharrell is not being cynical but rather synesthetic—he’s hearing things, which means he’s seeing things, and he’s wondering whether there is still enough time for the Clinton campaign to see these things, too.

“Most Americans?” he says. “It’s a tight race. It’s not ‘most Americans.‘ ” He goes on, referring to Trump as “him.” “Logic does not work against him. Scandal does not work against him. Every time you talk about him, you are keeping him in the press.” Kwan nods politely, diplomatically, neither agreeing nor disagreeing. You can’t help but get the sense that Pharrell wants to break through all this grip-and-grin Beltway formality and shout, “Wake up! Listen! The darkness is winning!” But regardless of how astute his political analysis may be—and, as we will learn a few days later, his realism was spot-on—it may be too late for anyone to listen.

Pretty soon the van goes silent. We look to the right and see the Trump–Pence press plane. It is parked here at the same airport, with the candidate’s famous slogan painted on the side. There is a muted charge of frustration in Pharrell’s voice, and a noticeable undercurrent of sadness, as he says, turning his gaze away from the plane: “Make America hate again.” Looking back now, it cannot be said that the rest of the evening on the campaign trail felt like a carnival. It cannot be said, no, that the inevitability of victory hovered in the air. At Raleigh’s awkwardly named Coastal Credit Union Music Park at Walnut Creek amphitheater, we go backstage. Clinton is there.

“So, we’re just waiting for Senator Sanders,” she says. If you happen to be blessed with a kind of synesthesia that allows your brain to translate sentences into emotions, her words sound like this: I have been on the campaign trail for eight hundred years. Along comes Bernie, with his Vermont snowdrift of hair and a suit so rumpled it looks cubist. He walks into Pharrell’s dressing room, the one with the picture of Carl Sagan taped to the snack table, and gives him a sort of avuncular half-hug. “Hello, how are you doing?” Sanders says. “Is there a bathroom around here?” Then he is gone. Clinton hovers in the hallway for a few seconds.

For a moment, Pharrell looks uncharacteristically hesitant. He leans in toward the Democratic candidate and asks her whether she’d be open to posing for a selfie with him. “Yeah, whatever you want,” she says. They squeeze close together and make goofy faces. Posing for selfies is, of course, one of the most common reflexes of our era, yet for someone as thoughtful as Pharrell, the practice is slightly cringe-inducing. “I’m so embarrassed I just asked for that picture,” he says afterward. “I would never do that.” Later, Pharrell will refrain from posting the selfie on his Instagram account.

Clinton and Sanders briefly retire to their dressing rooms. A Clinton operative materializes in Pharrell’s zone. “Who is Pharrell’s person to talk to?” she asks. “Can we have him come out to ‘Happy‘? Can we have him come out to ‘Happy’ onstage?” If you happen to be blessed with a kind of synesthesia that allows your brain to translate silences into interior thoughts, the silence in the dressing room sounds like this: Oh, wow, you guys are really thinking outside the box, aren’t you?

But ever the diplomat, Veazey nods yes. “Happy” will be just fine. “To me, the old definition of leadership is ‘Look at me, I’m a leader,’ ” Pharrell is telling the crowd of more than four thousand from the stage in Raleigh. “But the new definition should be ‘No, actually, look at you—I’m listening.’ ” These words will come to seem prophetic, but not in the way that he would have wanted them to. By the time the election is over, Trump’s victory will make it all too apparent that a whole lot of people—campaign aides, pollsters, pundits, reporters, your friends on Facebook—were not listening to much of anything outside the gleaming silo of their own echo chamber.

It will turn out, as it always does, that political campaigning and musical hit-making have a great deal of overlap. Both enterprises ultimately depend on being open to the signals—on receiving what’s floating around in the air. Pharrell’s understanding of this verity is evident in the showman like way he milks the audience. He gets to a line about “a country where all men and women were created equal,” but he leaves a perfect wait-for-it beat in between “men” and “women.” And then he says “women” again and the crowd doubles its whooping, and then he says “women” one . . . more . . . time and the power of hearing “women” in triplicate works the crowd into a happy victory-lap frenzy.

Before long, though, he’s back on the tarmac at the airport, wandering alone in the darkness as he takes a business call prior to his flight home to Los Angeles. Tomorrow he’ll wake up at home with his son and his pregnant wife. On the plane, I notice that his wedding ring is curiously loose—instead of being secure around his finger, it wobbles. He occasionally even places the gold ring between his teeth. I ask him about it. Pharrell tells me that Helen has a similar band, and that the rings are meant to communicate that “what we have is much more than they can see.” The rings are hollow. Inside each one, invisible to the eye, their respective birthstones jingle and tumble: diamonds for Pharrell, rubies for Helen. The rings, you see, make a kind of music. Pharrell holds his ring right up next to my left ear. “The stones are on the inside,” he says. “Listen.”