Pharrell Williams Is Finally Happy

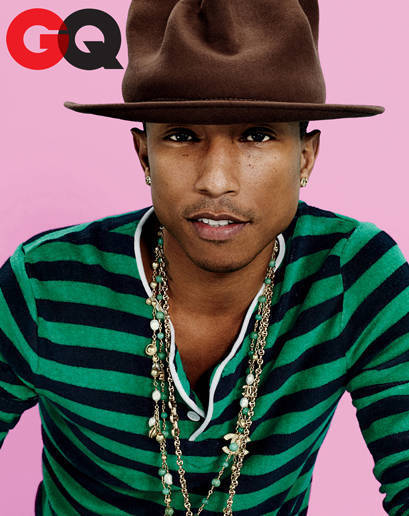

By Zach Baron. It might seem crazy what we’re about to say: Pharrell Williams, the ageless 40-year-old mega-producer, is about to have his biggest year yet. GQ’s Zach Baron spent a few days in the once and future Neptune’s orbit to find out why—after years of hit-making and money-raking—Pharrell says he’s just now figured it all out. Clap along, everybody. Photograph by Paola Kudacki.

Pharrell Williams looks like he’s been to many Zen gardens in his four decades on this planet, but in fact, today’s field trip will be a first. “We’ll be learning together,” he says, standing in the lobby of his Bel Air hotel, surrounded by outrageous ferns. The peaks of his Vivienne Westwood buffalo hat are huge and uneven, like the Alps. His face is—well, you know. He looks like he is never going to die. He has looked that way for forty years and counting.

Someone mentioned this Japanese Zen garden in Van Nuys, said Pharrell would like it. And so, on an overcast Tuesday in January in Los Angeles, we are off to look at some meditative trees. We wedge ourselves into an SUV and start driving, Pharrell in the captain’s chair, his cheerful, pixie-cut wife, Helen, beside him. His phone rings almost immediately, the name “Ush”—for Usher—displayed on its screen. They start talking. It is, at first, not at all clear what they’re talking about—just that Pharrell is trying to talk Usher into something preposterous involving horses.

“What I wanted to intimate to you is,” Pharrell is saying, “if the record comes out one month from now, the video comes out two months from now—you’re not late.” Okay, so: a song, one that Pharrell is apparently producing, “Year Of The Horse.” Chinese New Year is next Friday, and Usher’s worried about missing it entirely. But, Pharrell is saying, the Year Of The Horse lasts all year! Usher will be fine. Then he listens for a while. “Go and shoot the video,” Pharrell says finally. “That’s the only thing that I beg of you.”

Okay, so: a song and then a video. Usher talks for a bit, and then Pharrell cuts in again. “Look at what happened when Ginuwine did ‘Pony’ and he had the mechanical bull.” Classic music video Pharrell’s talking about here: Ginuwine saunters into a scuzzy roadhouse and commences a sexy, open-shirt routine right there on the stage. Then one of Ginuwine’s lady friends mounts a mechanical bull. “Now, that was Ginuwine. We’re talking about you, and bringing you to the rodeo world with a record that gives you the license to do that.”

Okay, so: a song and then a video…about the rodeo world? The ’90s-rap-video god Hype Williams should direct, Pharrell is saying. He talks about the synergy potential, all the different markets and classes and types of Americans that Usher could unite by bringing the gift of Usher into the competitive horse-riding arena. “This is a time for everyday people!” Pharrell says.

You can tell Usher is unsure there on the other end of the line, for reasons that seem pretty sensible, actually. But this is what Pharrell does. He is a cloud boxer. He is a genius of capitalism. He’s spent the past two decades selling you things you didn’t think you wanted but turned out to want very much. Very likely he once persuaded you to attempt a trucker hat, or a kickflip, or the music of No Doubt. His catalog could play literal hours before reaching a song you hadn’t heard before.

He is one of the two or three most successful producers of our time, a man who makes hits out of sinister pockets of silence and bits of other people’s songs and cell-phone ringtones and the golden sounds of the ’70s. The composer Hans Zimmer will later tell me a story about working on The Amazing Spider-Man 2 soundtrack, composing in a room with Pharrell and Johnny Marr, and watching Pharrell write an entire song on his cell phone in five minutes. Zimmer and Marr were just sitting there, arguing about chord changes, Zimmer says, “and by the time we’re finished, he’s written a fully formed song.”

On the phone with Usher, Pharrell is building to a kind of crescendo. “Let’s speak metaphorically through the rodeo world!” he says, urgently. “I fucking held a lamb in a Robin Thicke video. And people were into it!” What he really did in that video, for Thicke’s “Blurred Lines,” was sing to the lamb—You the hottest bitch in this place— but it’s true, people were into it. It is sometimes hard to recall what Pharrell has done that people weren’t into. He’s spent the past year chasing “Blurred Lines” with Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky”—in the process becoming one of the very few artists in history to hold the No. 1 and No. 2 spots on the Billboard charts at the same time—and more recently, “Happy,” the contagiously cheerful song from the Despicable Me 2 soundtrack that he is now repurposing as the lead single for his second solo album, G I R L.

He disembarks from the car, eases Usher off the phone with some final stirring images of glory in the corral, and together we walk into the Zen garden. There are bonsai trees and ducks. We pause outside a bamboo forest and marvel at a little waterfall. “I figured out why it’s so Zen here,” Pharrell says finally, lingering by the garden’s exit. “A lot of the species don’t move. They just age, gracefully. The beauty is in the strength, and in the stillness. It’s stimulating to not be stimulated.”

Back in the car, he plays G I R L for me. At this moment, nobody knows the record even exists. He’s grinning, skipping through songs on his iPhone. Listening to it is like mainlining a good mood. It’s like a Zen garden of smiles. It has preposterous lyrics about courtship—Taxidermy is on my walls…I’m a hunter!—and guest spots from Daft Punk and Justin Timberlake and Miley Cyrus. It’s like nothing Pharrell has ever done before, because Pharrell has never before bothered to make an entire album of disco-inflected, ’70s-soul-addled sex songs aimed at the entire global female population, which is his stated aim this time around. It is in fact so likable and persuasive that it has the disorienting effect of making a lot of Pharrell’s back catalog as a producer and artist—a catalog that has given me and probably you an unquantifiable amount of joy—sound, well, a little mean. Or if not mean…cold? Lacking in warmth?

Which is basically what I say, a bit hesitantly, after the SUV deposits us at lunch in Hollywood. Pharrell, you learn pretty quickly, is not much for looking back—he’s an arrow that only points forward. Plus, there is no shortage of evidence of him looking delighted, performing that back catalog, much of it on yachts. So it’s startling when he begins nodding.

G I R L isn’t his first solo record, he reminds me. That came in 2006. The year he made singles for Gwen Stefani, Ludacris, and Beyoncé, among others. He put out his own long-awaited, flamboyantly braggadocious rap record, In My Mind, and—“Crickets,” he says. He got outsold by Destiny’s Child exile LeToya Luckett and a fucking compilation, Now That’s What I Call Music! 22. It was baffling—a guy who could make a hit for an Ikea shelving unit couldn’t make a hit for himself. Except Pharrell is no longer baffled by it at all. “I wrote those songs out of ego,” he says. “Talking about the money I was making and the by-products of living that lifestyle. What was good about that? What’d you get out of it? There was no purpose. I was so under the wrong impression at that time.”

What’d you think the purpose of those songs was then? “I didn’t realize you should have a purpose. I thought you just did it just to do it.” Do you think that’s why the record didn’t sell as well as other things you’ve done? “Yeah, totally. It was the universe saying, ‘Look, you have a voice, you have an opportunity. What are you going to do with this?’ ” Was the universe saying that even before your solo record came out?

“Yeah, but I couldn’t hear it. The money was too loud. The success was too much. The girls were too beautiful. The jewelry was too shiny. The cars were too fast. The houses were too big. It’s like not knowing how to swim and being thrown in the ocean for the first time. Everything is just too crazy. You’re like, flailing and kicking and whatever, and you know what happens, don’t you? You sink. My spirit sank. I just felt like, ‘Fuck, what am I doing?’ ”

After In My Mind failed, he says, he decided that was it—“The solo-artist path was not for me.” As a producer, he was used to “being the guy next to the guy.” He figured he’d just go back to that. As he shifts in his chair, the tangle of chains around his neck clinks softly. Were you unhappy, in retrospect? “Of course.”

Pharrell doesn’t read much—he likes Wes Anderson movies and Coen Brothers movies and Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, stuff about misfits and science and outer space. But lately his favorite book is Paulo Coelho’s 1988 novel, The Alchemist, about an Andalusian shepherd boy’s search for his “personal legend”—nominally a chest full of treasure, but more generally his purpose in life, the thing he most wants to be. The book, Pharrell says, is a way to make sense of his own life.

As a child he finds that he has synesthesia, sees colors when he hears sounds. When he thinks about his childhood it comes back to him burgundy and baby blue, in strings of numbers and letters. His mother would sign notes to him with the numerals 143. It took him years to figure out what she meant. One letter, four letters, three letters: I love you. After Pharrell was born, his mother waited ten years to have a second child, and then ten more to have a third—no accident. “My mom is weird,” Pharrell says fondly. She was a schoolteacher before she retired. His father’s name is Pharaoh, who was named after his father, also Pharaoh.

This is Virginia Beach in the ’80s, a place vibrating at some mystic frequency—Timbaland, the other major producer of the era that would make Pharrell a star, just so happens to go to the same church. “We used to be up in Timbaland’s bedroom, where he would make his beats. And his dad would be in the other room. When that shit got too loud, he would be like: ‘Tim! Turn that music down!’ ” If the house had collapsed at that moment, we would’ve lost so much. We’d all be on antidepressants.

Pharrell “was the different guy,” says Pusha T. of Clipse, a Virginia Beach friend from those days. The different guy meets another different guy, Chad Hugo, a Filipino navy brat. He and Chad decide to call themselves The Neptunes and spend the next bunch of years producing for Teddy Riley, Blackstreet, SWV, whoever else would have them.

Finally, in 1998, The Neptunes write “SuperThug” for the Queens rapper Noreaga. It was the kind of beat that was about to make both Neptunes absurdly wealthy—a psych-rock riff played on a clavichord, disorienting drums, hardly any bass at all. Pharrell remembers walking into a club in Virginia after the song came out, “and it just hit so hard. They were like, ‘Fuck is that?’ I’ll never forget, like, dudes throwing chairs and shit.” He watches a small riot break out to his song and knows he is going to make it.

He buys a Lexus, then a Porsche, and because he’d been a backpack rapper first—anti-jewelry, pro-consciousness, allergic to stunting—he rides around in the Porsche with a backpack on. He begins connecting weird neural paths through pop culture—songs The Neptunes wrote for Michael and Janet Jackson would instead end up, say, in the hands of Justin Timberlake and Britney Spears, torches passing in the form of 808 claps and abrasive siren noises and teen lust. With N*E*R*D, the pop-funk-rock-rap-whatever-Steely-Dan-is group he starts with Hugo and another high school friend, he blazes a misfit trail that will later make possible Frank Ocean, Tyler, The Creator, and dozens of other unconventional musicians.

“Being a young black kid, especially at that time,” Tyler says, “I was different from all my other peers. So when I seen that this dude was saying he was open to rock and jazz and fucking skateboarding and all this other stuff that I was interested in, I was gravitating toward it because it was like: ‘All right, I’m not the only black dude who’s probably called weird every fucking day.’ ”

The Neptunes win Grammys that Pharrell barely remembers winning. A survey in August 2003 finds that the Neptunes are responsible for a full 43 percent of songs played on the radio that month. The boy who worshipped pop culture as a kid basically becomes it. Snoop’s “Drop It Like It’s Hot,” ODB’s “Got Your Money,” Jay Z’s “I Just Wanna Love U (Give It 2 Me),” Fabolous’s “Young’n (Holla Back).” You could fill a museum with Neptunes work from this era. The songs sound like misfiring fax machines, like old Chuck Brown songs, like pager ringtones. They sound like outer space.

He moves to Miami for the women and the weather and just loses himself in the wild rich current of it all. He has custom jewelry made—a solid-gold BlackBerry, a gold skateboard chain, a gold N*E*R*D chain, a jewel-studded pendant made in the form of a KAWS figurine. It was beautiful, the things he would do and say. He had turned his mind to being the best possible version of the worst possible guy, and we were all just witnesses. You can watch a video from 2006, Pharrell guesting on BET’s Rap City, promoting his solo record, achieving peak Pharrell-ness in the form of bejeweled nerd-icon: On the show he freestyles for a while and then fumbles in his pocket, finally pulling out a Rubik’s Cube, covered in diamonds on all six sides. He holds it out to the camera. It rotates and gleams in the light.

Just a quick aside here, about the diamond-covered Rubik’s Cube: It was so great when Pharrell had the diamond-covered Rubik’s Cube. Over lunch in Hollywood, I ask if he still has it, and he says yes, but these days it doesn’t come out much. “I don’t wear big, crazy stuff” anymore, he says. What do you think about it now? Does it make you feel awesome, that you had a diamond Rubik’s Cube? “No, I was out of my mind. It was ridiculous. But that’s how caught up I was.” You can leave it to your son. “Here’s a diamond Rubik’s Cube. This is your inheritance.” He gives me a skeptical look. “No, hopefully his inheritance is a great education and a positive outlook on life,” he says. Then he stands up to walk across the street and get a cupcake.

Ask him if getting married or turning 40 has changed him and he’ll tell you not at all. He nods at Helen, his wife, and she smiles back. “No, that’s just—that’s my bestie,” he says. It’s a day later; we’re sitting outside his studio in Burbank, the breeze warm, the sun bright overhead. He’s trying to explain how he got to where he is now—to “Get Lucky” and G I R L and whatever third or fourth or fifteenth act he’s about to commence. Mostly, he says, the past few years felt like business as usual—producing for Miley Cyrus and Kendrick Lamar, making accessories for Louis Vuitton and Moncler, collaborating on a sculpture with Takashi Murakami, raising his and Helen’s 5-year-old son, Rocket. Somewhere in there he flew to Paris and recorded a couple of songs with Daft Punk. He went into the studio with Robin Thicke, wrote and recorded “Blurred Lines” in about a half hour, kept it moving.

And then, in the spring of last year, he got a call from Daft Punk’s label, Columbia. “And they’re like, “Look, we know that you’re not interested in doing another solo album. But we know that you’re going to change your mind. Even if you’re not ready now, we know you’re going to change your mind. And since we know that, we’d like to get ahead of it and change your mind and tell you, “Look, here’s a deal. Go make whatever album you want to make.” ’ ”It took some convincing. But by the time he signed, he already knew what the album would be, what it’d be called, how it would sound. “I instantly knew that the name of the album was called G I R L, and the reason why is because women and girls, for the most part, have just been so loyal to me and supported me.”

I ask him what he means. “There is no breathing human being on this planet that did not benefit by a woman saying yes twice,” Pharrell says. “Yes to make you, and yes to have you. Point-blank. If women wanted to cripple the economy, all they gotta do is not go to work.” You mean work like…? “Period. Work at work, work at home. Okay? If they wanted to end our species, cripple our species—seriously! Like, women can look out into space at all the stars and go, ‘You know what? I can actually end all the human life on this planet right now. All I gotta do is just say no.’ There’s a huge value placed on that—you know, on something so simple like if all our talk-show hosts late at night all were women, that’s a very different world.”

He’s gotten older, he says, and so have some of the people who listen to his music. “Man, you gotta see the 60-year-old women dancing to ‘Blurred Lines,’ and they know it’s about them, and they don’t care what you think, and they’re going to come over here and tell you that that’s their record.” He pauses, so we can both behold that fact for a second, and we do. “So when I write a song on In My Mind called ‘How Does It Feel?’ ”—that’s the one that goes See me on the TV, the cuties they wanna fuck—“man, what was I talking about? That wasn’t joy. That was just bragging. I wanted to be like Jay. I wanted to be like Puff. Those are their paths. I got my own path. But I didn’t know what my path was. I knew that I was meant to do something different. I knew that I needed to inject purpose in my music. And I thought that was my path. I didn’t realize that like, from ’08 up until now was like, training. Like, keep putting purpose in everything you do. Don’t worry about it; just put purpose in there. At the table Pharrell suddenly breaks into song, singing his hook from Jay Z’s “So Ambitious”: The motivation for me, is them telling me what I could not be. Oh, well! Then he stops just as abruptly, and says again: “You know what I’m saying? Inject purpose. Inject purpose. Inject purpose.”