![]()

In honor of her debut album, Kaleidoscope, turning 20-years-old, Kelis will embark on a tour to celebrate the record she announced on her Instagram account, sharing the tour poster with all the dates. Tickets for the shows are on sale since Friday, November 22. Kelis also sat down with i-d to talk about The Neptunes and her debut album ’Kaleidoscope’. “It was a time when everybody — especially black female artists — was being boxed in doing one thing. I was never good at that anyways,” says Kelis. The album didn’t sell millions:

It debuted at No. 144 on the Billboard 200, and “Caught Out There” reached No. 54 on the Hot 100. Radio said she didn’t fit on R&B stations — “’Black people don’t listen to it,’” she recalls being told — “I kept saying from day one that I’m consistently inconsistent. It only makes sense when you’ve got a body of work. On top of that, it’s packaged in this black skin, and it was just too much. So for [me and The Neptunes], we didn’t care. We were like, we like all of it, we’re musicians. As long as there’s someone to listen, I’m going to keep doing it.”

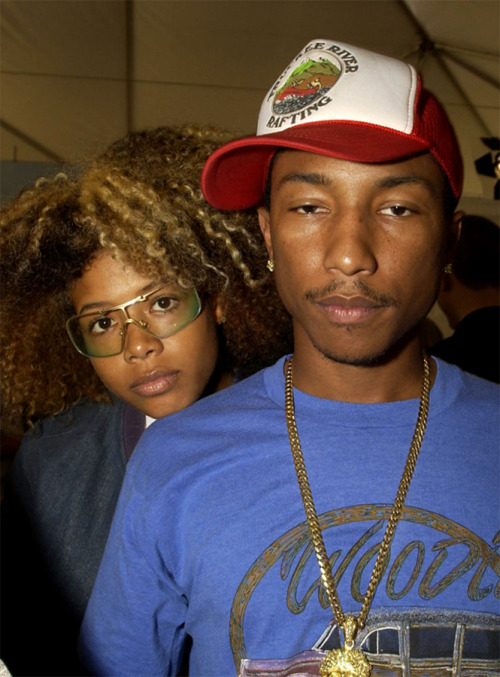

It was through her friend Markita, who raps on Kaleidoscope’s “Mafia”, that she met Pharrell and cold-auditioned for him in a stairwell singing The Fugees’ rendition of Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly”. Pharrell invited Kelis down to Virginia, where they cut a few songs including “No Turning Back” to take to labels. Industry magnates like Sylvia Rhone, then at Elektra, passed — they just didn’t get it, it was too out of the norm for them — but she ended up signing with Virgin and returned south to finish the album. At the time, Virginia was a breeding ground for music that side-stepped convention with a futuristic bent, namely with the rise of fellow Virginians Timbaland and Missy Elliott. Still, they were operating outside of the pressures of the music industry, and created at will.

They treated sessions like a day job, recording from 10am to 3pm, drawing directly from experiences no matter how far out. The mean-mugging “Mars”, for example, came from a conversation where Pharrell encouraged Kelis to write about watching a documentary the night before about inhabiting the planet. The topline on “I Want Your Love” was inspired by the theme from The Price Is Right, because she grew up watching it. Even the album art laid it bare: her naked body painted in a rainbow patchwork quilt, her hair a bright orange brushfire as she gazes upwards. (Originally, she wanted the portrait to be a silhouette of her frame, but the label turned it down.)

it took Kelis years to understand the scope of Kaleidoscope, not just in how it impacted others but also herself. When they were recording the album, The Neptunes were cultivating an artistic legion under their Star Trak imprint, which included artists like Clipse and Rosco P. Coldchain. “It came off very puritanical at the time,” says Kelis. But, “in retrospect, it wasn’t, because I was robbed blind.” It’s an age-old industry tale. Kelis explains that she was too young to question any of the business machinations. The label told her that the album would revert back to her in 20 years, something she couldn’t even fathom at the time, but what it meant, now that the time has elapsed, was that the album would revert back to themselves.

“Basically they’ve taken all of my publishing. I had no concept of royalties or publishing. I didn’t understand that my voice would be distinguishable and so it would matter,” she says. Virgin told her that royalties would be split evenly between her, Pharrell and Chad. That didn’t end up being the case. “Fast-forward 10 years and I didn’t think for one second, did I get paid for that? Were they fair to me? Did they give me what they said they were going to give me? Someone might argue that I was wrong, since I didn’t ask the right questions. It’s not a new story, it happens all the time.

Unfortunately, it happens to women a lot, it happens to black artists a lot. We were Star Trak. I was Star Trak for life,” she says, throwing up the Star Trak hand signal. “I was like, this is what it is, this is fun. It was supposed to mean something. And then to find out later it meant nothing and was just the same old rhetoric and rigmarole that we’re always hearing about, that it was essentially a modern day Motown? Yeah, you’re freaking amazing and you’re talented and interesting, and you have nothing, because you didn’t know to ask for anything. Whose fault is that?”

“People thought it had something to do with the music. It had nothing to do with that,” she says. “It had to do with the fact that I really made a decision. I was really pigheaded back then too, I was young and because I didn’t come into the game having to sacrifice the music, I was not going to start at that point. I was like, what? Go fuck yourselves.” Wanderland only came to streaming this past June; Kelis had no idea it had even been put on services until someone pointed it out to her on Instagram.

“Every single record I’ve had to fight for, because no one agreed at the time, but the people who really love music have always stood with me,” she says. “That’s the thing. To be someone like myself who’s used to fighting — and I’m OK with it — it’s been really comforting and solidifying and validating just to say that every single record I’ve had, there have been people who respect the music and that have always nodded to me. That made it so that I don’t care if I sell two records or two million records.”

“The funny thing is, Kaleidoscope doesn’t fit in anywhere,” she says. “It literally cemented me into musical history forever and I know that. It changed my life and the life of music for that era, because it made it so that black girls could look different and sound different and be different. It became about the artistry because it had to. Everybody understood that it had to live somewhere… I’d rather be critically acclaimed because it’s so off, rather than having everyone like you right now and tomorrow they don’t know who you are. I don’t need that. This is perfect for my personality. It just works out this way because this is who I am.”